The War Against God: Top Three Promethean heroes in Literature

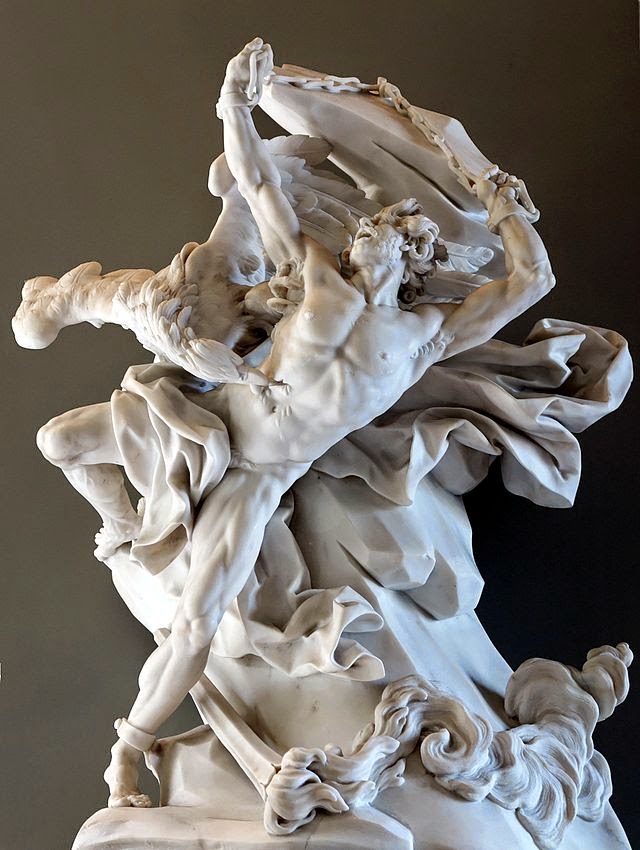

It started with the ousted Titan, who stole fire from the God’s and gave it to humanity. Punished for his iniquity and generosity in equal measure, Zeus, had him chained to a rock for all eternity, while birds devoured his liver. Then there is the Fallen Angel himself, Lucifer also aptly known as ‘the Bringer of Light.’ His first appearance, Genesis, in the slippery form of a serpent. Picture Eve standing before the tree of knowledge, pride of place in the Garden of Eden and being told: ‘The day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.’ If the answer is food for thought, then surely knowledge is a good thing? And if fire lights up darkness, then it is a cooking utensil of some capacity. Classical and Religious, the two archetype blasphemers of literature, who defy the gods out of their love of humanity, but there are more. Here are my top three:

Satan, Milton’s Paradise Lost

Surely the most humane and complex Satan ever seen yet. As Blake declared: ‘'The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true Poet and so of the Devil's party without knowing it.' True poet? We can only assume Blake means a writer obligated to truth and sincerity. Milton, like all great artists, can’t help but be a humanitarian, and unwittingly instills this in his diabolical creation.

Nevertheless we first find Satan, post-rebellion, chained to a lake of fire down in the deepest reaches of Hell. Fitting punishment for a disastrous coup, and a presumptuous challenge to Jehovah’s might. Yet despite the new lodgings Satan will not seek forgiveness, nor kneel. He declares: ‘Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven [...] Here at least we shall be free [...] Awake arise or be for ever fallen.’ These are the words of a emancipator.

Milton also notes Satan is Romantic soul, and quite willing to admit he possesses ‘dauntless courage,’ capable of ‘remorse and passion,’ and that despite his new lodgings he and his fellow brethren can ‘ease out their pain by work and endurance.’ Again this suggests a humanitarian spirit of triumph in adversity. A pragmatic attitude to say the least, which would be well adduced in heaven, hell and indeed earth.

However, like any latter-day revolutionary, Satan is not perfect. He is prone to rashness, pride and ambition. He is also overzealous with his guns, which is why he is locked down in the inferno in the first place. Flashback to the war in heaven: ‘Chariots and flaming arms and fiery steeds [...] Those deep throated engines belched [...] with outrageous noise the air and all her entrails tore.’ Alas, the Devil has graduated from his days as the wily serpent, he is now a gristled soldier and statesman a democratic one at that. Of course he has not had the luxury to read Animal Farm and is unable to foresee his revolution is doomed to failure. However as it stands, we have to admire his motive, for he believes election should not be based on divine precedent, but native equality.

God created the world and a lovely little garden and decided something was missing. Out of boredom perhaps, not to mention clay, he moulded our ancestor Adam. Adam also has his grievances, for we find him in Eden already apostrophizing the silent sky: ‘Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay to mould me man? did I solicit thee, from darkness to promote me. or here place in this delicious garden? [...] Inexplicable thy justice seems!’

And here we come to the crux: Adam’s argument is the same as Satan’s. This shows one of two things: Either God is a shoddy artisan and made a man, who is a little too rebellious, and a little too much like those traitors below. Or, more likely, Satan is a little more humane than angelic, a tad more human than divine.

Both Adam’s words and Satan’s speeches are for us earthlings, for we too are thrown into the world, conscripted to live life and we make the best of it come what will. What’s more, lest we forget, there are communities and individuals in all parts of the world who really are disenfranchised. Christopher Hitchens quite rightly labelled God A Kim Jong Il presiding over a North Korea, and we the oppressed multitude. Satan speaks for them and for us, who also wonder at the incomprehensible laws of the universe.

At last at one late point Satan stops for a moment to meditate on his madness: ‘The Evil one abstracted stood from his own evil and for a time remained stupidly good,’ and here Milton reveals his conceit. If Satan is good in the abstract, then he is bad in the real. Why? Because God’s abstract kingdom nevertheless has the ability to throw out real jail-time and punishment. Satan’s predilection for being ‘stupidly good,’ reveals his innate worth. He has become bad by circumstances and this is similar to us human beings. Like him we are trapped in the real world of cause and effect, and this is why we are both victim and victimizer, guilty and innocent at the same time. If we all lived in the abstract, then of course we would also be ‘stupidly good’ but we don’t. We live in the real world with real problems. As such Satan shows us, the evils of the world are not metaphysical anomalies, but readily explainable by reason. Not only is Milton party to the devil without knowing it, the devil is party to humanity (but perhaps in this case he does know it)

Captain Ahab, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick

The deranged captain of the Pequod whaling ship is leading his fellow sailors on insane quest through the Pacific ocean to hunt down and kill the mythical white whale Moby Dick. Captain Ahab is rightful namesake to his Old Testament predecessor: The wicked demon worshipper and King of Israel who while in command committed ‘more evil than all the kings before him’ and even more wickedly all ‘in the sight of the Lord above.’

So we welcome Captain Ahab who ascends the throne of blasphemy. What better way to coronate his new status, than a ritual baptism in fire, for it is out in a lighting storm the hero becomes Prometheus and Lucifer combined: ‘Look aloft! cried Starbuck. The Corpusants! The Corpusants! All the yard arms tripped with pallid fire; and touched with each tri-pointed lighting rod with three tapering white flames, each of all three masts was silently burning.’ ‘Mark it well’ Ahab bellows: ‘I now know that thy right worship is defiance [....] Thou clear spirit of fire thou madest me, and like a true child of fire, I breathe it back.’ This captain is marked for martyrdom.

On deck he is a cantankerous disciplinarian: ‘a hard driver’ is old Ahab, who has ‘driven one leg to death, and spavined the other for life.’ He also displays a morbid disposition: ‘joy and sorrow, hope and fear seemed ground to the finest dust [...] in the clamped mortar of Ahab’s iron soul [....] His whole life become one watch on deck.’ So what for that? Despite his difficult personality the captain is never truly evil. In fact his heart is good. We are told ‘from beneath his slouched hat Ahab dropped a tear into the sea; nor did all the Pacific contain such wealth as that one wee drop.’

Clearly one of those tragic heroes, a sick suffering soul, without much hope of a happy ending. And yet where does his blasphemy lie? The answer resides in Moby Dick. For this is not simply any ordinary sea creature, but the primordial Leviathan created by God in the first six days of creation. As such it is personification of God’s omnipotence, and Ahab knows it: ‘The white whale swam before him as the monomaniac incarnation of all those malicious agencies which some deep men feel eating in them [...] All that most maddens and torments [...] All the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil, to crazy Ahab were visibly personified and made practically assailable in Moby Dick. He piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all general rage and hate felt by his whole race [...] And as if his chest had been a mortar, he burst his hot heart’s shell upon it.’

Needless to say, Ahab’s can only conceive of God as the only true Devil, for it is the very whiteness of the whale that scares him the most. White is the ‘crowning attribute of the terrible.’ ‘the very veil of the Christian deity’ yet the most ‘appalling to mankind,’ because it is also the colour of God’s absence and our loss.

Ahab is Prometheus and aims to bring colour and light back to the world. His hatred for Moby Dick is the sum of humanity’s hatred and fear of all the riddles that haunt this mortal life: Old age, sickness, suffering and death, all witnessed on the backdrop of the arbitrary Laws of the universe.

Towards the end, Ahab at last reveals his essence: ‘I feel deadly faint, bowed and humped as though I were Adam staggering beneath the piled up centuries since paradise [...] Whose to doom when the judge himself [should] be dragged to the bar?’ ‘Were I the wind I’d blow no more on such a wicked miserable world.’ Why such a negative view you might ask? and the captain replies: ‘Ahab never thinks he only feels, feels, feels!’ ‘God only has the right and privilege [to think] and our poor hearts throb.’ Ahab is not interested in intellectual philosophy, all he knows is real heartfelt emotion. He rejects the cosmic order on account of his fellow mortals, who are made to bear the indiscriminate whims of fortune, and out of love for humanity, hunts down the tyrant God personified in that audacious white whale Moby Dick.

Ivan Karamazov, Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov

James Joyce once said: ‘The Brothers Karamazov made a deep impression on me [....] Madness you may call it, but therein may be the secret of his genius[...] I prefer the word exaltation, exaltation which can merge into madness. In fact all great men have had that vein in them; it was the source of their greatness’ Dostoevsky’s seminal masterpiece is now considered one the greatest works of the Western Canon. Admirers include, Freud, Kafka, Rowan Williams, Pope Benedict, and even Albert Einstein. As for the Karamazov’s, they are a dysfunctional family, of impassioned men, but it is Ivan who towers above all.

‘Ivan is a sphinx,’ ‘Ivan is a tomb’ ‘Ivan is a riddle’ ‘Ivan is not one of us’ ‘People like Ivan are like a cloud of dust.’ So the pronouncements follow our Promethean hero, yet every grave must contain its treasure, and every puzzle must be placed. After meeting his youngest brother Alyosha in the pub, Ivan yields up his secret: ‘I have lost faith in life [....] Everything is a disorderly, damnable, and perhaps devil-ridden chaos.’ Whats more of God’s majesty he admits: ‘Although I know it exists, I don't accept it at all.’ However, like all Promethean heroes he cannot shake off his divine heritage. He admits: ‘like a child I believe that suffering will be healed and made up for [...] That in the world's finale, at the moment of eternal harmony, something so precious will come to pass that it will suffice for all hearts, for the comforting of all resentments, for the atonement of all the crimes of humanity.’ For most that should be enough, but not for Ivan: ‘Though all that may come to pass, I don't accept it. I won't accept it. [...] That's what's at the root of me, Alyosha; that's my creed.’ Alyosha being a recently cloistered Monk quite rightly calls this Rebellion of the Satanic form, but Ivan’s war against God is really a humanitarian one.

He remarks to Alyosha: ‘You see, I am fond of collecting certain facts, and, would you believe, I even copy anecdotes of a certain sort from newspapers and books, and I've already got a fine collection.’ What follows is a list of atrocities. Stories of rape, torture and infanticide, child abuse, and murder, and genocide. After working himself into a masochistic frenzy Ivan cries: ‘Listen! If all must suffer to pay for the eternal harmony, what have children to do with it?’ ‘While there is still time, I hasten to protect myself, and so I renounce the higher harmony altogether. It's not worth the tears of that one tortured child who beat itself on the breast with its little fist and prayed in the stinking outhouse, with its unexpiated tears to dear, kind God! [...] They must be atoned for, or there can be no harmony.’ ‘From love for humanity [...] I hasten to give back my entrance ticket.’

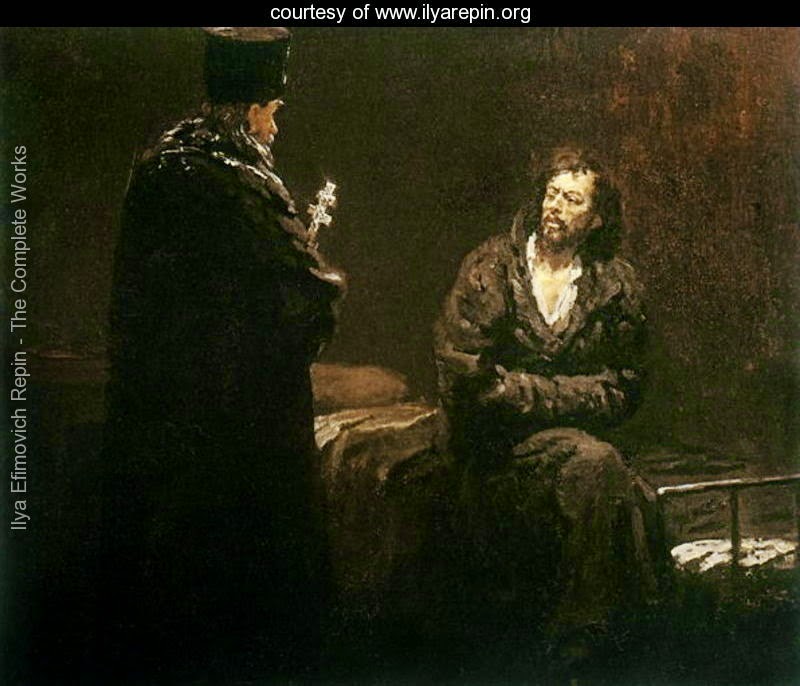

Alyosha contends, What about the our Saviour. Doesn’t he count for something? Ivan is ready, not just with more grievances, but armed with a parable that will rival any of Christs. He calls his story: ‘The Grand Inquisitor.’ The ‘story is laid in Spain, in Seville, in the most terrible time of the Inquisition where fires were lighted every day to the glory of God.’ In the midst of such horrors the Son of God decides to reappear: ‘In His infinite mercy He came once more among men [....] The sun of love burns in His heart [...] He holds out His hands to the people, blesses them, and a healing virtue comes from contact with Him.’ Yet all is not well: ‘the Grand Inquisitor, passes by the cathedral [...] An old man, almost ninety, tall and erect, with a withered face and sunken eyes.’ He is outraged by Jesus’s return and quickly arrests him. In the dungeon they confront each other, and the cosmic battle between Hell and Heaven begins.

The Inquisitor cries: ‘Is it Thou? [....] Don't answer, be silent [...] I know too well what Thou wouldst say. And Thou hast no right to add anything to what Thou hadst said of old [...] why has Thou come to hinder us?’

Now for scripture.Matthew 4:1-11, Mark 1: 12-13, and Luke 4:1-13. The devil is out in the the wilderness of the Judaean desert ready to confront Christ: Temptation One: ‘If you are the Son of God, tell this stone to become bread [...] and Jesus answered, It is written: Man shall not live on bread alone.’ Yet in today’s world, what could be more appalling than poverty? The inquisitor ratifies: ‘There is no crime, and therefore no sin; there is only hunger. Feed men, and then ask of them virtue!’For the second temptation: ‘The devil led Christ up to a high place and showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world And he said to him, I will give you all their authority and splendor [...] Worship me, it will all be yours.’ Christ retorts ‘worship the lord your god and serve him only.’ Yet what can be more sensible than uniting a divided earth under one banner? The inquisitor remarks: ‘We took from Him Rome and the sword of Caesar, and proclaimed ourselves sole rulers of the earth [...] We shall plan the universal happiness of man.’ For the final temptation, ‘the devil led Jesus to Jerusalem and had him stand on the highest point of the temple, If you are the Son of God, he said, throw yourself down, for it is written He will command his angels concerning you to guard you safely’ Christ retorts, ‘Do not put the Lord your God to the test.’ However, what could affirm life more than a true miracle? The inquisitor snaps: ‘Thou didst refuse [....] Thou didst proudly and well, like God; but the weak, unruly race of men, are they gods? [...] Is the nature of men such, that they can reject miracle, and at the great moments of their life, the moments of their deepest, most agonizing spiritual difficulties, cling only to the free verdict of the heart?’

The inquisitor is triumphant: Feed the world, rule the world, and present miracles to the world, and the world will be healed. He declares:‘Know that I fear Thee not [....] I awakened and would not serve madness. I turned back and joined the ranks of those who have corrected Thy work.’ ‘Or Dost Thou care only for the tens of thousands of the great and strong? [...] We care for the weak too.’

Of course, Ivan’s parable is just that. Like Prometheus this Karamazov must pay the price for challenging the God’s majesty. He descends into full blown psychosis, and instead of meeting Jesus, he meets Satan in the form of a terrible hallucination. And it really is terrible for this is a ‘paltry devil’ who wears ‘a brownish reefer jacket, rather shabby’ and ‘who goes to the public baths.’ This is not an Archfiend to match Ivan’s expectations. So it follows Ivan bears humanity’s suffering alone. His gift of fire that he stole from the Christian God, cannot be shared amongst his peers, but instead consumes his heart.